|

||||||||||||||

|

ROBERT CRAIS: INTERVIEW - THE TWO MINUTE RULE |

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

What was the inspiration for this book? THE TWO MINUTE RULE began as an Elvis Cole novel. I was thinking about the nature of Elvis’s clients—the people who come to him for help and why they would need a private investigator. When you are the victim of a crime, you go to the police, but what if you were someone who couldn’t go to the police—maybe you didn’t trust them or you thought they might be suspicious of you? I was working on this character when I realized that only one type of person could be so totally alienated from society; completely outside the system and friendless—a criminal. That’s when I had Max Holman and I knew this wasn’t an Elvis Cole novel. The real power of the story is Holman’s isolation. He can’t turn to Elvis Cole for help. He’s a criminal, he has no money, he’s unsophisticated--but if he wants to learn the truth about his son’s murder, ex-con Max Holman has to investigate the police. When the book opens, Holman is completing a ten year prison sentence for bank robbery. Why did you make him a bank robber? In the late 90s, six men robbed the Dunbar Armored Car company here in L.A. of $18.9 million dollars in cash. This was the largest cash robbery in U.S. history. They were caught and are now in prison, but the police were only able to account for about four-and-a-half million dollars. The rest of the money is missing. Fifteen million in cash, and it could be anywhere. Learning about the Dunbar case led me to research other robberies where large sums went missing and haven’t been recovered, and most of these robberies were bank jobs. A hundred thousand here, two or three hundred thousand there— Finders keepers. Exactly. You have this missing cash that might be buried in someone’s yard or stashed in a storage shed or hidden in a dusty attic. The notion of all this lost, unclaimed cash is alluring— Like buried treasure. It’s mythic. The Lost Dutchman’s Mine. Sunken galleons. People devote their lives in the search for unclaimed treasure. These things became the background for Holman’s story. The atmosphere comes across as being authentic. How do you set about creating the characters and settings? I immerse myself in the character. I work myself so deeply into the character that I feel what he feels and see what he sees until I don’t quite know where I end and he begins. When you are feeling what the character feels, you can describe the world honestly as he sees it through his eyes. With Max Holman, I had to tap into my own feelings of alienation, loss, and regret. If I were an actor, I would call this ‘method acting.’ So I’m a ‘method writer.’ And, of course, thorough research is mandatory. Holman is a convict and a career criminal, yet he’s a very sympathetic character. Was it hard to create a person with his background who was so human and sympathetic? When I first told my publisher and agent the concept for THE TWO MINUTE RULE, they were concerned that Max would be unsympathetic, but I never saw him as anything less. Here’s this guy coming off a lifetime of bad choices, lost opportunities, and squandered relationships; consequently, he has no one to love him because he has lived a loveless life-- I loved the sense of regret he carries. This book has a very melancholy feel to it. His regret defines him. At the point in his life when we meet him, Holman regrets the choices he made and suffers the losses that came with those choices. He doesn’t make excuses for himself. He has taken responsibility for the mess he made of his life, he’s paid his debt to society, and now he’s trying to move forward. His expectations are pretty low, but lofty at the same time--lofty for a man like Holman; he wants to salvage the remains of his life. I admire his courage. He’s not swaggering and arrogant, but he’s a tough guy. Holman’s tough, sure. He was a car thief, a bank robber, and a drunk; he ran with criminals and punks since he was a kid, but there’s no swagger left in him. See, that’s part of his maturity and regret. He knows that being able to beat up someone is no worthwhile indicator of manhood, so why take pride in it? When he was young, Holman would have taken pride in being hard and ripping off people, but no more. Now, he’s embarrassed for having felt that way and ashamed for how he acted. But you gave him a temper and we see flashes of violence-- That’s who he is. If I wanted to create a character who was true, then I had to be true to his nature. Holman might be regretful and reformed, but he is still Max Holman with all of Max Holman’s life experiences. He’s a coarse man who learned to use his fists early and that hasn’t changed. The difference now is that he’s trying to control himself. That was one of the things I enjoyed most in the book, how you show Holman struggling with his nature. For me, this is the subtext—really, the foundation—of this story: Holman’s struggle against himself; this alienated outsider who not only has to struggle against the police and the situation, but also himself. I read in another interview that you often use things you see and feel in your own life in your fiction. Was that the case with this novel? Absolutely. We’re back to ‘method writing.’ Is there any of us who doesn’t regret a choice we’ve made or a loss we’ve suffered? It’s the job of the writer to tap into those personal experiences and transform them into fiction. Is the Two Minute Rule real or something invented for the book? It’s a term coined by the FBI. It’s a reference to the minimum arrival time for first responders to a robbery-in-progress. The actual time will vary according to locale and traffic conditions and other factors, but two minutes is the usual rule of thumb. Two minutes doesn’t seem like enough time to rob a bank. Two minutes can be a lifetime. There are many different ways to rob a bank—-note jobs, which is where the bad guy hands a demand note to a teller; take-overs, which is where bad guys go in with guns and literally take over the bank; tunnel jobs; and inside jobs. Two minutes might not seem like much, but some of these guys work as efficiently as an elite military unit. Two take-over guys who worked Florida and Georgia stole millions of dollars and never once stayed in a bank longer than fifty-five seconds. Think how precise and tight they had to be. They would enter a bank, take control of all those people, empty the teller drawers and the vault, and split in less than a minute.  Earlier,

you said research was mandatory. Did

you do any particular research for

the book? Earlier,

you said research was mandatory. Did

you do any particular research for

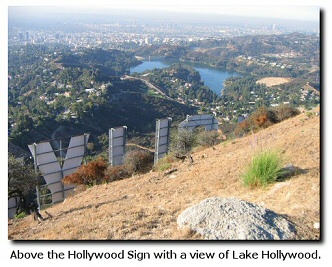

the book?Research for a novel like this is essential. I’ve kept a file about bank robbery for years, especially in regards to unrecovered funds. I interviewed FBI agents and prosecutors; I visited the FBI’s Los Angeles Field Office; I even explored the Los Angeles River channel and hiking routes to the Hollywood sign. It was on two such trips where I found perfect settings for major scenes in the book—a murder site and a place for buried secrets. I also had to do extensive research into what Holman’s life would have been like in prison and during the release process. When you’re not writing, what do you do to relax? I run. I go to the gym. I like to do physical things. Do you ever miss writing television? No. I wish I had come into my own with the novels earlier in my career, but there you go. I’m more suited to novels, disposition-wise. What do you mean, come into your own? I wrote two novels during my television years. They were terrible, unpublishable, so bad that I’ve never let anyone read them. See, that was me teaching myself how to write a novel. That was my learning curve. You wrote them while you were writing television? Yeah. I’d get up early, work on them on the weekends or between jobs. When I moved to Los Angeles it was never my intention to exclusively write television or screenplays. I wanted to write everything and TV was just part of it. I had every intention of writing more short stories and writing novels, but the TV just sort of took over. It is an enormously demanding profession. But eventually I grew discouraged with television and novels were my long-term goal, so I tried to write novels. Thing was, I didn’t know how to write a novel. What television shows do you enjoy watching these days? Lost. I’m a big J. J. Abrams fan and I’m totally addicted to this show. And Veronica Mars. I didn’t watch Veronica during its first season, but these friends of mine hammered me about how good it was—they were relentless. So my wife and I finally Netflicked the dvds and, man, they were right. We watched the first four hours back to back and now we’re hooked. Veronica rocks. Since you like it so much would you want to write one? Oh, no. God, no. See, I can watch a show and enjoy it, and while I’m sitting there I’m probably thinking, hey, this idea would make a groovy episode or I’d like to do such and such with this character—I’m a writer; I can’t help having ideas for these things—but I know way too much about the process of writing an episode of television and I don’t care for it. Maybe Elvis Cole could help Veronica with a case. He might like to date her. Me, I’d rather write books. I’ll leave Veronica to Rob Thomas. He’s doing a great job. Was it fun writing the script for Hostage? In many ways, yes. It was fun to adapt one of my novels into a screenplay and it was certainly fun to revisit those characters again. I loved Jeff Talley. And Mars. But they ended up bringing in other people and changing everything and the movie was, well, the movie.  Los Angeles

almost seems like another character

in your books. How important is it

to you to get the location and sense

of place right in a novel? Los Angeles

almost seems like another character

in your books. How important is it

to you to get the location and sense

of place right in a novel?Character and place are one and the same. You cannot have a fully formed character—a living, breathing character—unless that character reflects the place in which he or she lives. Take Holman. He grew up in Los Angeles, his memories are of this place, but he’s been in prison for ten years, and when he returns to LA the city he returns to is different. He sees it with a newcomer’s eyes, yet he is anchored by his memories. The smells and flashing colors of Olvera Street, the views of the city from the Hollywood sign—he sees these places with new eyes even as his memories define who he was. And the room he takes—his first ‘civilian’ home in ten years—it is little more than a cell because it reflects the prison he hasn’t yet left behind. As a writer, I draw inspiration from setting. The cinnamon and grease smell of a churro will give me an insight into the character; the gray concrete walls of the L.A. River will make me flash on the oppression one feels in prison. If I can feel it, I can convey it. Those sensory cues evoke mood and character as much as they evoke place. Yet your prose is stripped down— Too much detail is bad. You can drown your story in detail; you can absolutely destroy the narrative. Part of the craft—maybe the biggest part—is in learning how much is enough.  Would you

be happy living anywhere else in the

world? Would you

be happy living anywhere else in the

world?No. I love Los Angeles. I would not be me without it. Let me ask something about your first home, Louisiana-- Yes? Katrina. You’re from Louisiana. You were in New Orleans when the city was evacuated. Would you tell us what happened? I had flown to Florida the week before. Katrina was a tropical storm then and still in the Atlantic. A friend of mine from Metairie—that’s like a suburb of New Orleans on the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain—was going to meet me for a few days of scuba diving, but Katrina started creeping toward the Keys. That was well below us, but by Wednesday the dive boats even as far north as Palm Beach and Jupiter were canceling their charters and tying off. My friend was supposed to join me Wednesday night, but we made a new plan—instead of him flying to Florida where this nasty storm was ruining the water, I would fly to New Orleans where the water was nice and calm in the Gulf— Oh, man! So that’s what we did. The next day—Thursday—I flew to New Orleans, my friend picked me up, and we drove east to Panama City on the Gulf Coast. Ten or eleven miles out from shore, the floor of the Gulf is littered with wrecks. We spent Friday wreck diving, and that’s when Katrina clipped past Florida and entered the Gulf. She was still southeast of us, but she ramped up as soon as she hit the warm water. There was still an unknown quantity to her path on Friday—the weather people were saying she might stay to the south and miss Louisiana— So you stayed in Panama City? Saturday morning was bizarre. The waters off Panama City were smooth as glass. The sky was a brilliant, cloudless blue. We picked up a charter boat, went out six or seven miles on this glassy water, but once we splashed we could see the difference—the water beneath the surface was so torn up that the viz was down to eight or ten feet and the currents were surging. We didn’t know it at that time, but Katrina had veered hard to the north and was making dead on for New Orleans.  When did

you find out? When did

you find out?As soon as we reached shore. My friend’s wife called and told him that the evacuation order had been issued and the highways were going to be contra-flowed at four o’clock—that’s when the traffic on the in-bound highways is reversed, so you can’t enter the city; you can only leave. It was one o’clock when we got the word and we were a five hours from New Orleans. We threw everything in the car and blasted for the city. I was on the cell phone, booking flights out of New Orleans as we drove, hoping I could get out that night, but the airlines kept canceling the flights out from under me. I didn’t believe we’d be able to get back into the city, but my buddy knows every back road and short-cut in the state. We made it to Metairie at ten or eleven that night, started packing his truck, and left early the next morning along with a couple hundred thousand other people. That was Sunday. The drive on I-10 from New Orleans to Baton Rouge is normally a little more than an hour, but on that Sunday it was a ten-hour trip. We hopped to the west side of the river and used every farm road we could find. We made it up to Baton Rouge in three and a half hours, where I got one of the last flights out of BR before they closed the airport. Did your family make it through the storm okay? Several relatives and friends lost their homes. My friend’s house in Metairie where we spent Saturday night was flooded. They’re all living in Baton Rouge now while they go about rebuilding. I’m just thankful that none of them were harmed. Everyone got out in time.  Have you

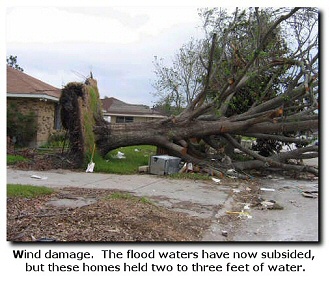

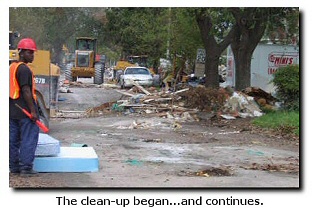

been back since the storm? Have you

been back since the storm?Yes. It’s worse than anything you’ve seen on television. You cannot appreciate the magnitude of what happened through your television—the scale diminishes the destruction. You have to see it to understand. Will you write about it? I can’t not write about it. The effect on me and so many of the people close to me is too dear. Also, Lucy and Ben Chenier are from Louisiana. This event will have affected them and it will have to be dealt with. I’m looking forward to writing about it. I am anxious to deal with this thing. Let me jump back to your writing. THE TWO MINUTE RULE is your thirteenth novel. Does writing the novels get harder or easier? More difficult. Definitely more difficult. The more I learn about writing, the more I realize that I don’t know a damned thing, so I dig harder and deeper to write well. Life as a best-selling writer must have many things going for it. What do you like best about it? Knowing that I’ve been able to touch so many people, and that they enjoy what I’m doing. The readership has grown consistently with every new book. I get mail through the website from England, France, Italy, Japan, China, Australia, Israel, Africa, all over—I’m in twenty-six or twenty-seven countries now. It’s amazing. If you had to sum yourself up in a single word, what would it be? Writer. Thanks, RC. No problemo. |

||||||||||||||

|

Contents of this web site are copyright 2022 by Robert Crais. Photo of Robert Crais by Greg Gorman Website designed and maintained by Dovetail Studio |

||||||||||||||